Today, Xi'an is a "must-see" city on the global tourist circuit and built into every package tour of China. The reason is simply the presence of the Terracotta Warriors, created to protect the mausoleum of the First Emperor, Qinshihuang. This book was written to enhance a visit to the city by providing a general cultural history and illustrating the role of the other great dynasties which contributed to its culture and fabric, in particular the Han, Sui and Tang, but also the later Ming (who built the extant city wall) and Qing. The story is brought up to date until the discovery of the Warriors in 1974, and consequent growth of the tourist industry.

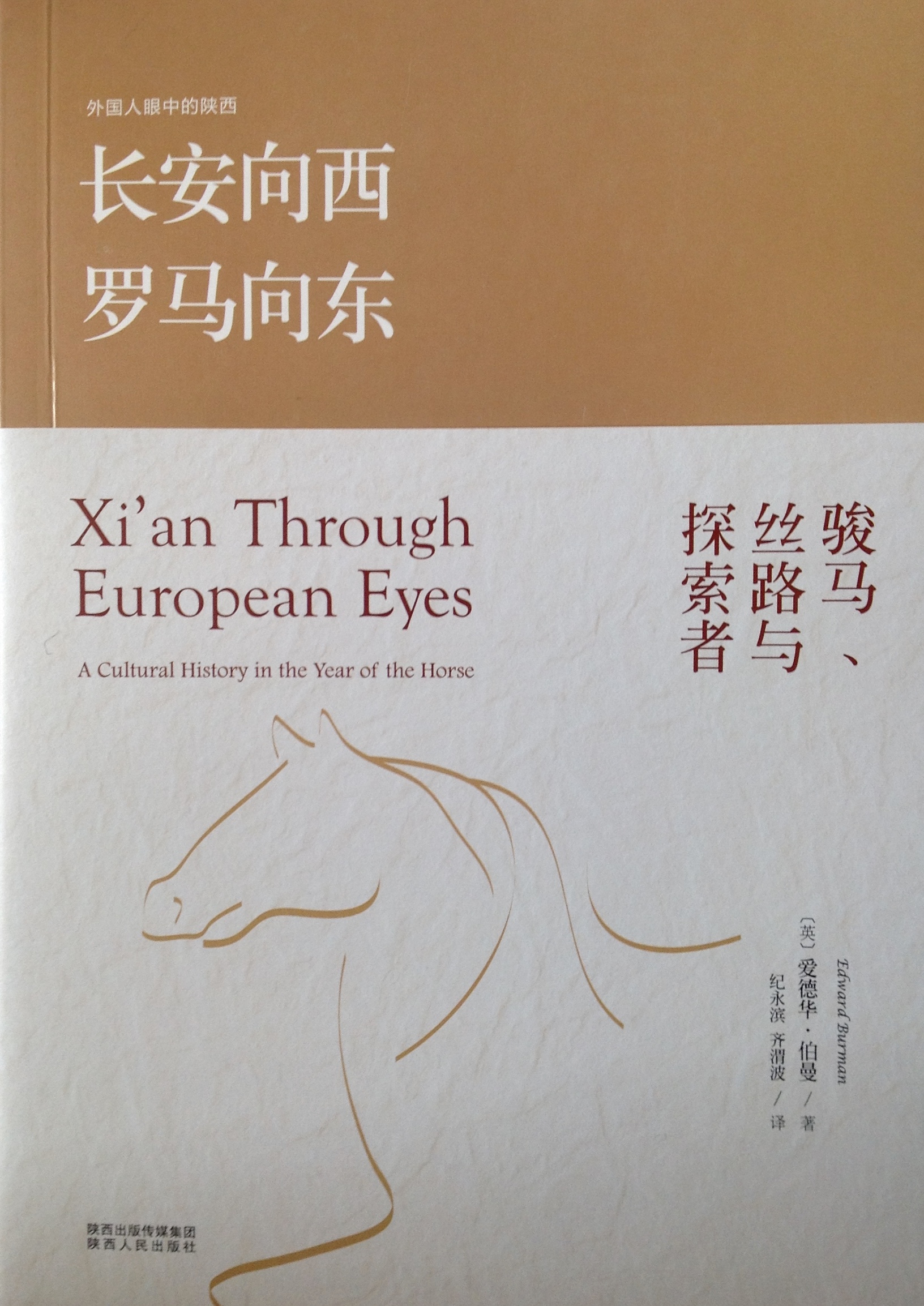

It was first published in a Chinese translation by Shaanxi People's Press in 2015, with the title 长安向西 罗马向东, and with the English subtitle Xi'an Through European Eyes, and also in a privately sponsored luxury edition of 81 copies printed on hand-made paper and bound in silk. In early 2016, it was published in the English original in China,

The book was written in the Year of the Horse, which is especially appropriate since the horse played a vital role in the history of Xi’an. More than any other factor, the horse symbolised military power in times of war and social status in times of peace. There was no greater mounted warrior in Chinese history than the Han general Hu Qubing or the Tang warrior Li Shimin, who both contributed enormously to the later success of their respective dynasties, while a later edict of the Tang emperor Gaozong actually forbade riding to artisans and merchants. Many of the more than eighty illustrations in the book are photographs of horses, especially those of the Han and Tang dynasties.

A "heavenly" or "winged" horse at the beginning of the Spirit Way at the emperor Gaozong's mausoleum.

It was the discovery of “heavenly horses” in Central Asia by the imperial envoy Zhang Qian and their deployment by Emperor Wudi which led to the military supremacy of the Han dynasty and their effective control of China for four hundred years; it was commerce in horses which balanced trade with silk and contributed to the prosperity of Chang’an, as Xi’an was then known; and it was depictions of the horse which characterised the sculpture and paintings of early Chinese art under the Tang dynasty. One example unites these multiple roles: the six magnificent relief sculptures of his favourite warhorses made for the tomb of Li Shimin, later the Emperor Taizong (626-649). These reliefs, of mounts whose names and deployment in military campaigns are known to us from historical records, still survive - four in the Beilin Museum in Xi’an, and two in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (henceforth referred to as the Penn Museum). They personify the power of the city: the military success of the future emperor in the saddle, the wealth which enabled the early Tang to purchase horses from the west to sustain his campaigns, and the sophisticated sculptural techniques used to make them. Paintings and poems of these horses were also made.

Behind this symbol of power and wealth, two main geographical features account for the foundation of Xi’an and its growth into one of the greatest cities on earth under Taizong and his successors. Firstly, its location on the loess plain which offered - and still offers - excellent conditions for agricultural development when it is also provided with abundant water; secondly, its position on a natural route along the valley of the River Wei which linked the central plains of China with the western regions, and on to the rest of the world in the days before long-distance sea travel. These two factors facilitated the evolution of ancient Xi’an as the key Chinese city of the great Silk Road: food and water to sustain a large population, and perfect conditions for a great commercial centre. The rise of the dynasties which ruled Xi’an and dominated China for centuries, in particular the Qin, Han and Tang, was also made possible by these features. One of the reasons for the decline of this dominant role, and the relative decline of the city, was the rise of maritime commerce - especially under the Song, who for this reason shifted the capital eastwards to Kaifeng near the Grand Canal and then south to Hangzhou.

Trade in silk and other commodities had linked China with the West in the past, but China became known to ordinary Europeans in the seventeenth century with the publication of several significant books and the widespread use of porcelain and tea. Its major cities in our eyes were Beijing, Hangzhou and Guangzhou, then known as Peking, Hangchow and Canton - names which still exist in airport shorthand and trade fairs. Xi’an, in its many manifestations, distant from the eastern coast and its ports, never had a European name and was largely forgotten in that period.

The Governor's Yamen, from

So until the late 20th century Xi’an was seldom visited by travellers or writers. In fact neither Chinese from other cities nor foreigners knew much at all about the city. A rare European visitor in the 19th century could write: “It is old and isolated; so old that no one in China knows the story of its beginnings, and so isolated that the Pekinese speak of it as though it were a foreign country.” Outside China it was known to scholars of religion for the presence of the Nestorian Stele (although until 1907 even that famous monument stood exposed to the weather and was barely legible, in the grounds of a ruined monastery beyond the city walls). Then at the end of the year 1900 the city gained notoriety when the Dowager Empress Cixi retreated there from Beijing and set up a temporary court in the Governor’s yamen, or official residence. Thus a Danish explorer and journalist could describe Xi’an shortly afterwards as “… known generally as the place of refuge of the Chinese court during and after the Boxer troubles.” No mention of past glories, of the many imperial dynasties which had called the city their capital, or of the sites familiar to visitors today.

Yet this is where it all began. What the French doctor, poet, sinologist and archeologist Victor Segalen called the true China. In a perceptive paragraph he remarked a century ago that “The word ‘Chinese’, despite such a vast empire and twenty-two dynasties, with its disorders and tempests and foreign conquests, refers to a group of ideas, of men and things easily restricted, easily definable. Let us call Chinese all that is contained in the persistent development of the ‘Hundred Families’ of the Wei Valley. Everything else derives from that. It is an enclosed, non-southern China sculpted and mined in loess. Patriarchal, meticulous, fixed, already definitive, already imperial. This is the pure Chinese element.” In his book Through Hidden Shensi, (New York, 1902), the American traveller Francis Henry Nichols observed that the wealthier denizens of Xi’an were intensely aware of their past, rarely spoke about the events of the previous fifteen hundred years, and considered the Mongols to be modern usurpers. So we must agree, thinking of the early interest in less important monuments and discoveries further west, with the British diplomat Sir Eric Teichman when he notes just a few years later how curious it was “that this region has not received more attention from European scholars interested in these matters, since it contains the beginnings of everything as far as Chinese history is concerned.”

Getting there was tough. In the days before a rail link, several foreign authors noted that it was quicker to travel from Beijing to London or Paris (via Harbin and the Trans-Siberian Railway, from 1903), or even to New York, than to Xi’an. Teichman observed, travelling in 1917, that given the heavy traffic between Tongguan and Xi’an “it is one of the absurdities of modern China that no railway should yet connect Hsian, the metropolis of the North West, with the coast.” The experienced China hand Carl Crow, in his Traveler’s Handbook for China (1922), could write that Chengdu and Xi’an were both “so far from the ordinary and modern routes of travel that they can be visited only by those who are willing to extend their visits to the country and make special and often tedious arrangements or these interior journeys.” Even when the railway did bring a “modern route of travel” to Xi’an in 1934 the English travel writer Peter Fleming, whose brother Ian wrote the James Bond novels, reported that it was first necessary to obtain an official passport in Beijing to travel to and enter the city. After dark a further special pass was required to enter Xi’an from the station, and yet another had to be obtained from the provincial Governor in order to continue his journey westwards to Lanzhou. These matters absorbed so much time that it was virtually impossible for him to look around the city.

Still today, none of the celebrated Western travel writers has written at length about Xi’an. Few have even visited. For various reasons, including a series of revolutions and the virtual closing of the borders for sixty years up to the 1990s, there was minimal tourism and little business interest in modern times.

Press conference in Xi'an for the Chinese edition